A Week 1 Perspective:

In many respects, holding COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, echoes the issues that arose in last year’s COP28 in Dubai. Once again, the COP is held in a major oil and gas-producing country where the prospect of getting an agreement to phase out fossil fuels to tackle climate change is challenging, to say the least.

Baku is Europe’s oldest oil city, and its history of oil production dates back to 1837. By the beginning of the 20th century, half of the oil sold in international markets came from Baku, and today, oil and gas account for 95% of Azerbaijani export revenues. The wealth that has been accrued is evident in the splendid architecture and layout of the city, widely described as “The Paris of the East”. Some of the streets are among the world's most expensive shopping streets, and modern glass skyscrapers of various shapes and sizes adorn the city. As the President of the Republic said at the opening of COP29, ‘Oil and gas are a gift of God’. Naturally, this was not a statement that went down well with most of the 60,000 registered attendees, but an indication of what difficulties the 198 signatory countries to the Paris Agreement face over the coming week in reaching any meaningful accord.

Apart from these issues, the conference is beset by wider geopolitical problems. The recent election of populist and far-right politicians in several countries, the tensions provoked by the Ukraine war, and the stated intention of President-elect Trump to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement all conspire to make the negotiating environment very difficult. There is also the absence of senior politicians from the US, France, Germany, and Ireland, as well as an inexperienced EU Commission, all of which create a leadership vacuum. This is at a time when the world has had its first annual encounter with the 1.5oC warming level, and climate has demonstrated the catastrophic consequences that can be unleashed in many parts of the world, including Ireland.

The main focus of the COP this year has been to renew an annual fund to assist developing countries cope with the impacts of climate change predominantly caused by developed countries (such as Ireland). Of course, the occurrence of sudden extreme events is easy to comprehend in terms of fatal floods, heatwaves and storms. But slow onset events such as droughts are also part of the story. The original fund finally reached $100 billion in 2022, some 13 years after the pledges were first made. It is important to emphasise that this is not charity. It is rather reparations for losses and damage caused by the 10% of the world’s wealthiest people (such as Irish people) who are responsible for 50% of global emissions. It is also an investment in global sustainability for the next generation and minimising the geopolitical stability of enforced population displacement.

The ‘ask’ from the developing world is now five times greater at $1 trillion. It seems an astronomical figure, but some scientific estimates suggest that fair recompense should be 5 times greater even than this. It can be achieved with imaginative new contribution sources, such as small financial transaction levies. For comparison purposes, the revenue from soft drinks globally amounts to about $0.5 trillion!

It is poignant to hear the stories from the Small Island Development States. You can’t ask them to reduce their emissions since they have none. All you can do to stave off their demise, in some cases, is offer money to adapt to present and future extreme climate events. Ireland has a good record in this area. It enjoys a favourable reputation as an intermediary between developed and developing countries, not least due to its long involvement in development issues and its post-colonial shared experience with many of them. As part of a UN negotiating partnership, Minister Ryan and his counterpart from Costa Rica are centrally involved in gaining agreement on adaptation finance and ensuring that it is focussed on the most vulnerable countries. However, who benefits and who contributes is the crunch issue.

Ireland is also deeply involved in the negotiations on implementing the Loss and Damage fund established in COP27. This is rendered even more complicated by the structural arrangements of the COP, whereby blocks of countries are represented by a nominated spokesperson, like the EU (currently Hungary, but that’s another story!). However, these blocks date back over 30 years to the original UN agreements. For example, the G77 group of what was then developing countries included China and the major oil producers, as well as the Small Island Developing States. The world 30 years from now be very different, with different agendas to be reconciled under the UN’s unanimity requirement. A recent document signed by Mary Robinson and previous UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, among others, has questioned whether the COP is today fit for purpose. It has evolved into something different from that intended in 1992. Over 1,700 coal, oil and gas lobbyists have been granted access to Cop29. They quietly go about their business but are everywhere on the conference floor. Non-governmental environmental organisations' ability to counter well-funded oil and gas lobbyists is very limited. Calls for a reformed COP system are justified, but the big question is, what alternatives exist? A free-for-all is not an option. The famous Tragedy of the Commons essay by Garret Hardin, written some 60 years ago, reminded us that an unregulated commons brings disaster to all. Let’s hope that multilateral cooperation survives for now and that week 2 brings some rays of hope.

Week 2 – The Red Lines are laid out

The serious business at a COP begins midway through the second week. Many of the political leaders have returned home or, this year, disappeared from the G20 meeting in Brazil, and the national negotiators have gotten down to work. What should be more appreciated is the multiple strands of negotiations being carried out simultaneously. A dozen or more separate strands are involved, and it is common to see teams from the 190 countries represented here rushing around and trying to coordinate with their colleagues. By Wednesday of week 2, lengthy draft documents will be beginning to emerge. These are riddled with suggested amendments in phrases in square brackets. The negotiators must argue which should remain and which should be removed to produce a final agreed document. Here is where the red lines emerge and where potential deadlock occurs. Having sat in on some of these sessions as an observer, one cannot but admire the wordsmithing skills of some of the legal experts, especially from the oil-producing countries, who can seek to fundamentally change a sentence or paragraph to suit their interests by a strategically placed comma or semicolon.

The principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) was established in 1992 at the first Earth Summit, where the countries declared: “Given the different contributions to global environmental degradation, states have common but differentiated responsibilities. The developed countries acknowledge their responsibility in the international pursuit of sustainable development in view of the pressures their societies place on the global environment and of the technologies and financial resources they command.” In other words responsibility for causing climate change was accepted by the developed countries and an obligation to assist the developing countries cope with its impacts and develop in such a way that they would not worsen global climate change was implicit. The scale of financial transfers to achieve this has remained a bone of contention ever since, and the ‘ask’ by the developing countries has increased as the extremes of accelerating climate change have worsened.

The new finance goal sought by the developing countries is now $1.3 trillion. Although this sounds astronomical, it is in fact much less than the amount spent globally on fossil fuel subsidies. Nonetheless, it is a figure that the developed countries are baulking at, and while reluctant to share numbers, their offer is believed to be currently somewhere around $300 billion. Whether this will result in an ongoing deadlock is too early to say. One of the sticking points is also who the donor countries should be. The developing country bloc established in 1992 included China and the oil exporting countries. The poorest countries and the Small Island Developing States have very different needs from some of the countries that have become relatively affluent in their bloc over the past 30 years. A reluctance to break ranks further complicates negotiations with the global north. One possible landing point is for some countries that have become capable of providing finance, such as China and India, to offer south-south ‘voluntary’ finance to the poorest developing countries. The quality of the finance is also important, with grants being demanded instead of loans, which burden the poorer countries with long-term debt.

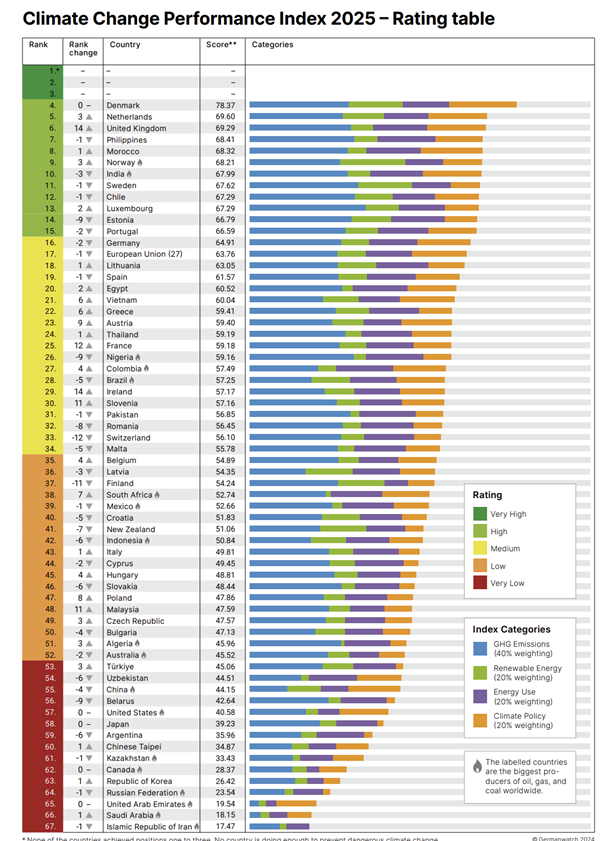

On a more local note, the annual ‘league table’ known as the Climate Change Performance Index was published today. Compiled by three respected organisations, this produces a report card for each country based on consultations they make with key organisations at a national level. Again, no country was deemed capable of doing enough to align with the Paris temperature limit, although the Nordic countries emerged as league leaders and several petrostates dominated the ‘relegation zone’. The full table is below. Ireland moved up 14 places this year due to receiving a medium rating in Renewable Energy, Energy Use, and Climate Policy, but a low rating in GHG Emissions. The full report can be seen at https://ccpi.org/.

In conclusion, the next 24 hours will determine if COP29 will deliver the goods sufficiently to retain trust between the 195 countries. Ultimately, only by multilateral cooperation can the existential problem of climate change be overcome. However awful the COP process is, the practical alternatives are not clear.

MGC, on behalf of Emeritus Professor John Sweeney of the MU Department of Geography and ICARUS reports from Baku, Azerbaijan