The impact of policy changes to reduce health inequalities in Ireland can take many years to take effect, according to Dr Jan Rigby from the Maynooth University Department of Geography.

Speaking at the 'Socio-Economic Inequalities in Mortality in Ireland Over Time and Place' conference, Dr Rigby presented a new analysis of death rates in over 400 locations across the country, which was conducted by researchers from Maynooth University. “While changes have been noted in some areas since 2006, due to factors such as an influx of young people, many of the patterns showing the highest and lowest death rates have persisted. The inequalities can be clearly seen, and it is vital that the commitment to reduce these remains at the top of our agenda,” Dr Rigby observed.

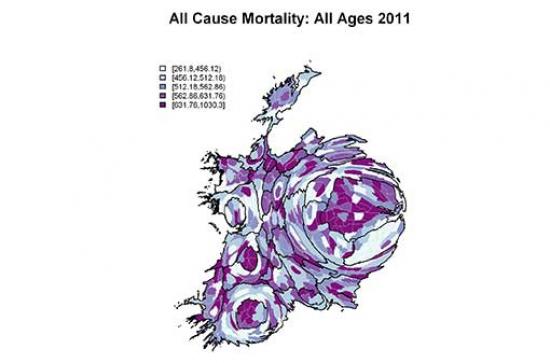

The findings signal that areas of deprivation have higher death rates for people of all ages. The areas with the healthiest populations, based on death rates, are more prevalent in Dublin—although the capital also includes the areas with the worst rates. There can be stark statistical differences between areas only a few miles apart, according to the research.

For the last three years researchers at the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), Maynooth University and Trinity College Dublin have partnered on the study, which systematically examines mortality patterns in Ireland and how they vary between socio-economic groups. Life expectancy in Ireland has been increasing for over half a century and statistics show that the rate of improvement increased during the economic boom around the turn of the century. However, recent research shows that this large improvement in life expectancy was not shared equally across social groups. Whereas life expectancy rates among male professionals, managers and the self-employed improved by 27% between the 1990s and 2000s, those among male working class groups increased by just 4%.

The geography of death rates for the years 2006-2011 shows that areas with very high or very low rates are found within the urban areas, particularly Dublin and Cork. This is true for death rates for all ages and all causes and for death rates for under-75s, which are known as 'premature' or 'avoidable' mortality. Such data indicates a measure of inequality, and assists policy makers in their aim to reduce the high mortality rates in areas where the figures are most extreme.

Research Findings:

- Between 1950 and 2012 life expectancy in Ireland grew by 15 years on average, from 66 to 81. This increase reflected real improvements in living standards and the adoption of better lifestyles, particularly due to reductions in smoking since the 1970s.

- The rate of improvement in life expectancy increased around 2000. Between 1996 and 1999 death rates fell by 5%, but between 2000 and 2004 they fell by 26%. Research suggests this improvement was due to improvements in the control of cardiovascular and respiratory conditions in the late 1990s.

- All social groups have experienced improvements in life expectancy since the 1980s. However, a growing gap has emerged in life expectancy between social groups. Whereas death rates among manual working class groups were 90% higher than among professional groups in the 1980s, the disparity had doubled by the 2000s.

- The growing gap between social groups largely reflects an increasing gap between non-manual and manual groups for deaths from external causes. Among male manual groups, death rates from external causes increased by a third, while decreasing by a quarter among professionals. Data from elsewhere suggests that increasing death rates from industrial and farming accidents during the economic boom may be important factors.

Policy Implications:

- The increase in life expectancy in Ireland over the last half a century reflects real improvements in living standards and improvements in lifestyle.

- Improvements in life expectancy were shared across social groups, but the rise in deaths from external causes may reflect a more dangerous work environment for manual and farming groups.

- The geographical variations, particularly for under-75 death rates, support the need to continue to focus on health inequalities.

Funding for the research was provided by the Health Research Board.