A Week 1 Perspective:

In many respects, holding COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, echoes the issues that arose in last year’s COP28 in Dubai. Once again, the COP is held in a major oil and gas-producing country where the prospect of getting an agreement to phase out fossil fuels to tackle climate change is challenging, to say the least.

Baku is Europe’s oldest oil city, and its history of oil production dates back to 1837. By the beginning of the 20th century, half of the oil sold in international markets came from Baku, and today, oil and gas account for 95% of Azerbaijani export revenues. The wealth that has been accrued is evident in the splendid architecture and layout of the city, widely described as “The Paris of the East”. Some of the streets are among the world's most expensive shopping streets, and modern glass skyscrapers of various shapes and sizes adorn the city. As the President of the Republic said at the opening of COP29, ‘Oil and gas are a gift of God’. Naturally, this was not a statement that went down well with most of the 60,000 registered attendees, but an indication of what difficulties the 198 signatory countries to the Paris Agreement face over the coming week in reaching any meaningful accord.

Apart from these issues, the conference is beset by wider geopolitical problems. The recent election of populist and far-right politicians in several countries, the tensions provoked by the Ukraine war, and the stated intention of President-elect Trump to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement all conspire to make the negotiating environment very difficult. There is also the absence of senior politicians from the US, France, Germany, and Ireland, as well as an inexperienced EU Commission, all of which create a leadership vacuum. This is at a time when the world has had its first annual encounter with the 1.5oC warming level, and climate has demonstrated the catastrophic consequences that can be unleashed in many parts of the world, including Ireland.

The main focus of the COP this year has been to renew an annual fund to assist developing countries cope with the impacts of climate change predominantly caused by developed countries (such as Ireland). Of course, the occurrence of sudden extreme events is easy to comprehend in terms of fatal floods, heatwaves and storms. But slow onset events such as droughts are also part of the story. The original fund finally reached $100 billion in 2022, some 13 years after the pledges were first made. It is important to emphasise that this is not charity. It is rather reparations for losses and damage caused by the 10% of the world’s wealthiest people (such as Irish people) who are responsible for 50% of global emissions. It is also an investment in global sustainability for the next generation and minimising the geopolitical stability of enforced population displacement.

The ‘ask’ from the developing world is now five times greater at $1 trillion. It seems an astronomical figure, but some scientific estimates suggest that fair recompense should be 5 times greater even than this. It can be achieved with imaginative new contribution sources, such as small financial transaction levies. For comparison purposes, the revenue from soft drinks globally amounts to about $0.5 trillion!

It is poignant to hear the stories from the Small Island Development States. You can’t ask them to reduce their emissions since they have none. All you can do to stave off their demise, in some cases, is offer money to adapt to present and future extreme climate events. Ireland has a good record in this area. It enjoys a favourable reputation as an intermediary between developed and developing countries, not least due to its long involvement in development issues and its post-colonial shared experience with many of them. As part of a UN negotiating partnership, Minister Ryan and his counterpart from Costa Rica are centrally involved in gaining agreement on adaptation finance and ensuring that it is focussed on the most vulnerable countries. However, who benefits and who contributes is the crunch issue.

Ireland is also deeply involved in the negotiations on implementing the Loss and Damage fund established in COP27. This is rendered even more complicated by the structural arrangements of the COP, whereby blocks of countries are represented by a nominated spokesperson, like the EU (currently Hungary, but that’s another story!). However, these blocks date back over 30 years to the original UN agreements. For example, the G77 group of what was then developing countries included China and the major oil producers, as well as the Small Island Developing States. The world 30 years from now be very different, with different agendas to be reconciled under the UN’s unanimity requirement. A recent document signed by Mary Robinson and previous UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, among others, has questioned whether the COP is today fit for purpose. It has evolved into something different from that intended in 1992. Over 1,700 coal, oil and gas lobbyists have been granted access to Cop29. They quietly go about their business but are everywhere on the conference floor. Non-governmental environmental organisations' ability to counter well-funded oil and gas lobbyists is very limited. Calls for a reformed COP system are justified, but the big question is, what alternatives exist? A free-for-all is not an option. The famous Tragedy of the Commons essay by Garret Hardin, written some 60 years ago, reminded us that an unregulated commons brings disaster to all. Let’s hope that multilateral cooperation survives for now and that week 2 brings some rays of hope.

Week 2 – The Red Lines are laid out

The serious business at a COP begins midway through the second week. Many of the political leaders have returned home or, this year, disappeared from the G20 meeting in Brazil, and the national negotiators have gotten down to work. What should be more appreciated is the multiple strands of negotiations being carried out simultaneously. A dozen or more separate strands are involved, and it is common to see teams from the 190 countries represented here rushing around and trying to coordinate with their colleagues. By Wednesday of week 2, lengthy draft documents will be beginning to emerge. These are riddled with suggested amendments in phrases in square brackets. The negotiators must argue which should remain and which should be removed to produce a final agreed document. Here is where the red lines emerge and where potential deadlock occurs. Having sat in on some of these sessions as an observer, one cannot but admire the wordsmithing skills of some of the legal experts, especially from the oil-producing countries, who can seek to fundamentally change a sentence or paragraph to suit their interests by a strategically placed comma or semicolon.

The principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) was established in 1992 at the first Earth Summit, where the countries declared: “Given the different contributions to global environmental degradation, states have common but differentiated responsibilities. The developed countries acknowledge their responsibility in the international pursuit of sustainable development in view of the pressures their societies place on the global environment and of the technologies and financial resources they command.” In other words responsibility for causing climate change was accepted by the developed countries and an obligation to assist the developing countries cope with its impacts and develop in such a way that they would not worsen global climate change was implicit. The scale of financial transfers to achieve this has remained a bone of contention ever since, and the ‘ask’ by the developing countries has increased as the extremes of accelerating climate change have worsened.

The new finance goal sought by the developing countries is now $1.3 trillion. Although this sounds astronomical, it is in fact much less than the amount spent globally on fossil fuel subsidies. Nonetheless, it is a figure that the developed countries are baulking at, and while reluctant to share numbers, their offer is believed to be currently somewhere around $300 billion. Whether this will result in an ongoing deadlock is too early to say. One of the sticking points is also who the donor countries should be. The developing country bloc established in 1992 included China and the oil exporting countries. The poorest countries and the Small Island Developing States have very different needs from some of the countries that have become relatively affluent in their bloc over the past 30 years. A reluctance to break ranks further complicates negotiations with the global north. One possible landing point is for some countries that have become capable of providing finance, such as China and India, to offer south-south ‘voluntary’ finance to the poorest developing countries. The quality of the finance is also important, with grants being demanded instead of loans, which burden the poorer countries with long-term debt.

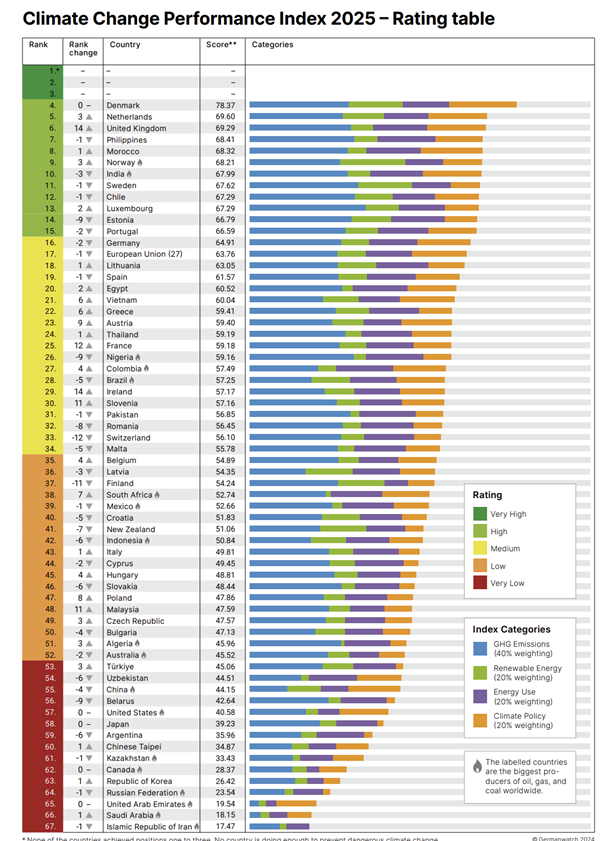

On a more local note, the annual ‘league table’ known as the Climate Change Performance Index was published today. Compiled by three respected organisations, this produces a report card for each country based on consultations they make with key organisations at a national level. Again, no country was deemed capable of doing enough to align with the Paris temperature limit, although the Nordic countries emerged as league leaders and several petrostates dominated the ‘relegation zone’. The full table is below. Ireland moved up 14 places this year due to receiving a medium rating in Renewable Energy, Energy Use, and Climate Policy, but a low rating in GHG Emissions. The full report can be seen at https://ccpi.org/.

In conclusion, the next 24 hours will determine if COP29 will deliver the goods sufficiently to retain trust between the 195 countries. Ultimately, only by multilateral cooperation can the existential problem of climate change be overcome. However awful the COP process is, the practical alternatives are not clear.

Week 3: COP29 Baku – The North-South Fault Lines that Scuppered Real Progress

At the final Plenary around 4 a.m. on Sunday the COP President, His Excellency Mukhtar Babayev brought down his gavel to signify the end of COP29. The intended scheduled end was some 36 hours earlier, and, not unusual for a COP, agreement among the almost 200 countries had not been reached in time. The sticking point was, as expected, the amount of finance the richer countries of the global north would provide to assist the poorer countries of the global south to cope with the climate breakdown inflicted on them. The main objective of this COP was to agree a new ‘quantum’ to replace the $100B per year agreed in 2009 (and only reached in 2022). In the intervening years, climate breakdown has accelerated, and coping with increased loss and damage has led developing countries to seek a renewal of funding extending to $1.3 trillion. Developed countries have baulked at this but refused to say what their floor figure was until the dying hours of the conference. When this figure finally emerged, it was $300 billion, to be reached by 2035, an amount described by some developing countries as ‘breadcrumbs’.

Of course negotiations to reach a compromise should have started in earnest 10 days ago. Many developed countries wanted to do this, but the influence of the Presidential team from Azerbaijan would appear to have stifled this. And so began a long night of negotiations to craft a new text. While some countries, such as Ireland, were progressive in their proposals, others were not. An imminent general election in Germany whereby a report that Germany was upping its aid to the developing world was clearly something that would be politically contentious in combatting the rise of the extreme right. Equally, the awareness that any US commitment might amount to nought after January 20th was in the consciousness of many. Geopolitical issues around Gaza and Ukraine also did not help. However, as usual, the main blockers were the oil producers, especially Saudi Arabia, who tried to undo some of the language around the fossil fuel transition agreed upon at COP28 in Dubai. Things became heated overnight with reports of a ‘lot of shouting’ among the developed countries. Even the EU (the EU Council is currently chaired by Hungary) came in for a lot of criticism.

It is a regular complaint of the developing countries that ‘they get us tired, they get us hungry, they get us dizzy, and then we come to terms with agreements that don’t truly represent the needs of our people.’ Multiple texts were issued for consideration by the Presidency during the course of Saturday. Accounts of bilateral negotiations, rumours of walkouts and disagreements swirled through the night. Supposed final plenaries kept being postponed. Ultimately a sum of $300 billion was offered to be reached by 2035. That’s around a quarter of what is currently spent globally on fossil fuel subsidies.

The winners of this COP are undoubtedly the rich oil-producing countries and the newly industrialised countries of Asia. These are still classed as developing countries under the outdated classification agreed in 1992. As such, they are not obliged to contribute to climate finance. Despite the traditional industrial economies such as the US, EU, Japan, etc., seeking to broaden the donor base, this came to nothing. China offered to voluntarily contribute to the most hard-pressed countries of the global south and may yet emerge as the next decade's main ‘climate leader’ should the US and EU go AWOL.

This has been the most difficult COP of the 15 I have attended. The lack of transparency from the Presidency and some of the developed countries jeopardised the outcome on several occasions. The final outcome does not please most of the nations in Baku. Indeed, the gavel was hurriedly banged down before the objections of major countries, such as India, were voiced. It is time for a reform of the operation to take place. Abolition would be too simple a solution since this is the only forum where large and small countries enjoy parity of esteem, and losing this multilateral approach would be unfortunate for the most vulnerable countries in the Global South.

What has been lost, however, is an appreciation of climate justice. I attended a presentation by a government minister from the Solomon Islands this week. A nation of 1,000 spread out islands, it is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change impacts and the second most at risk nation in the world for natural disasters. The Minister described poignantly how homes were being lost through rising sea levels, how wells were becoming salinized, and how young people were being reluctantly asked to consider moving to other islands. She also described how the rising sea level was washing away the graves of her ancestors, a cultural impact of significant proportions. Yet the Solomon Islands are a net carbon-positive nation, absorbing more of the world’s greenhouse gases than the minimal amount it produces. What do we in Ireland say to them about our seeming indifference to meet our climate obligations? Perhaps when our culture and way of life are threatened by climate change, our children and grandchildren will start asking hard questions of what our elected leaders were saying and doing in 2024.

MGC, on behalf of Emeritus Professor John Sweeney of the MU Department of Geography and ICARUS reports from Baku, Azerbaijan