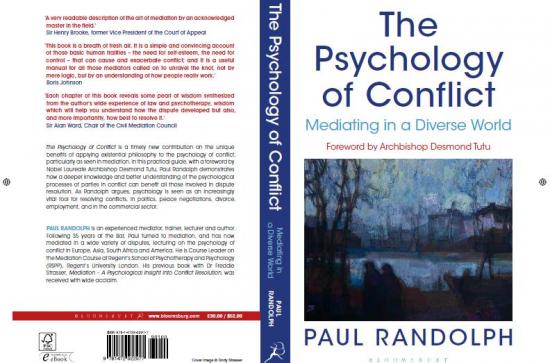

Paul Randolph’s new book, The Psychology of Conflict - Mediating in a Diverse World, has now been published by Bloomsbury, with a foreword by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and endorsements by Boris Johnson, Sir Henry Brooke, and Sir Alan Ward. Johnson writes “‘This book is a breath of fresh air. It is a simple and convincing account of those basic human frailties – the need for self-esteem, the need for control – that can cause and exacerbate conflict; and it is a useful manual for all those mediators called on to unravel the knot, not by mere logic, but by an understanding of how people really work.”

The book was launched at an International Peace summit in Regent’s University at which Nontombi Naomi Tutu, daughter of the Archbishop and renowned human rights activist was the plenary speaker. Paul Randolph presented at the Edward M Kennedy International Conference on Mediation and Restorative Practices in September 2014.

Paul’s article on “the Mediation Conundrum” is published below as an introduction to his book.

The Mediation Conundrum

Paul Randolph argues that it is time for some form of compulsion to mediate.

[Adapted from two articles published in the New Law Journal in April 2010 and February 2011 respectively]

The Problem

Imagine for a moment that Mediation is a product – a Carpet Cleaner - that can be purchased from any supermarket.

Almost all who have used it praise it highly. The product ‘does what it says on the tin’: it is cheap, it is quick, and in most cases it completely eradicates the stain; it rarely leaves behind unpleasant odours, is easy to use, and saves much time, cost and energy.

On the next shelf is another Carpet Cleaner called Litigation. Almost all who have used it are highly critical of it. It frequently fails to deliver its promise of success: it is extremely costly, very slow, and in most cases fails to eradicate the stain completely or at all; it nearly always leaves behind an unpleasant odour, is complicated to use, and takes up huge amounts of time, money and energy.

Yet people queue up to purchase Litigation, and shun Mediation. Why?

This bizarre situation, which defies all market trends, was confirmed by Professor Hazel Genn in her research into ARM, the Automatic Referral to Mediation pilot scheme at Central London County Court (‘Twisting arms: court referred and court linked mediation under judicial pressure’: May 2007), in which she found that in approximately 80% of cases, one or both parties objected to mediation. Research in other contexts also repeatedly shows that people are not as enthusiastic about mediation as the Government, the Judges, and the mediation community think they ought to be.

So what is it that drives the public to purchase in droves a product they know to be costly, lengthy and risky to use, in preference to one that is cheaper, faster and has little or no risk?

The Problem Explained

Many will argue that it is a matter of education, that there are still too many who do not know about mediation, and who merely need to be informed. This may be correct, but the sad fact is that UK mediators have spent much of the last 20 years attempting to inform and educate – firstly seeking to raise awareness amongst solicitors and barristers, then judges, the public, financial institutions, insurers and large corporations. Can one remain ignorant of Mediation in this age of Information Technology, where Google can identify any concept, fully define its meaning, and explain every variant of its use, in nano seconds? Or is it simply a case of the public turning a blind eye, and not wishing to know or to explore further?

Throughout history, Christian clergy, Rabbinical teachers, Muslim clerics, Buddhist monks, and Confucian philosophers have all sought to teach the essence of mediation. Abraham Lincoln’s 1850 notes for a lecture to his law students contained the following:

‘Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever they can. Point out to them how the nominal winner is often the real loser – in fees, expenses, and waste of time. As a peacemaker, the lawyer has a superior opportunity of being a good man. There will still be business enough.’

Why have all these teachings seemingly fallen upon deaf ears?

There have undoubtedly been a number of successful conversions in the UK, with many law firms, corporations and insurance companies now fully behind the concept. Even some judges have found that by referring all the boundary disputes to mediation, they relieve themselves of having to try some of the most tiresome futile and wasteful cases in their list.

But still mediation has not unleashed itself into or been accepted by the legal system in the way most would have hoped.

The Psychological Rationalization

The fault, dear Reader, lies not in our legal systems, but in ourselves.

As a species, we are not programmed to compromise, but rather to win – and in winning we want to see blood on the walls! This innate aggression is identified in Charles Darwin’s theory of the survival of the fittest. One needs only observe a baby fiercely kicking and screaming for its mother’s milk, to see how fierce this instinctive force can be when we do not get what we want.

But when litigants are in a dispute, the inherent aggression that creates our Darwinian ambition to survive, transforms itself into an even more acutely belligerent need to triumph over the opposition. We no longer act rationally or think commercially; instead we are driven by an emotional desire to comprehensively crush our opponent.

Such strong emotions are not confined to childlike squabbles over property boundaries or family assets. A survey in October 2007 conducted by the law firm Field Fisher Waterhouse, found that 47 per cent of company executives and in-house lawyers involved in heavyweight commercial litigation and who responded to the survey, admitted that a personal dislike of the other side had driven them into costly and lengthy litigation.

The Biological Explanation

There is a biological explanation for such behaviour: it is in the Amygdala, a small part of the brain that controls our ‘automatic’ responses. From an evolutionary perspective, it governs the “fight or flight” syndrome, associated with fear of attack. The amygdala reacts to the threat of attack by initiating the fight or flight reaction: it overrides the neo-cortex (the ‘rational’ thinking part of the brain) and physically precludes any reliance upon intelligence or application of reasoning.

In present day terms, of course, the attack which can bring on such a reaction is not a physical attack in the wild, but rather an attack upon values and personal integrity. In a legal context, few attacks can be more emotionally penetrating than an allegation of fault or lack of integrity, whether it be through negligence, or breach of contract.

It is for this reason that parties in dispute find themselves unable to approach the matter rationally or commercially. This is particularly so in the initial stages of the dispute, when the emotions are raw, self esteem has suffered a battering, and the parties are driven by feelings of anger, frustration, humiliation, and betrayal. It is at this stage that the lure of litigation is at its most powerful: for litigation offers everything a litigant yearns for: outright success, complete vindication, public humiliation of the other side, and lots of money!

It is therefore little wonder that mediation, with its inability to compete with such offers, falls a poor second in the disputant’s choice of a resolution process. It is only when money is hemorrhaging into the pockets of the lawyers, and the stress of protracted litigation is beginning to bite, that litigants start to consider alternative forms of resolution. Until then, they want their lawyer to be a rottweiler rather than a poodle, and the lawyers feel constrained to oblige.

The Arguments

So, is it time for us in the mediation fraternity, and all the supporting institutions which so ardently promote mediation, to resign ourselves to the fact that we will never fully succeed in persuading the majority to come to mediation merely by the use of education and logical argument? Should we not accept the futility of continuing to list cost and time savings, when the average litigant seems perfectly content to squander savings, fritter away corporate profits, deplete estates, and risk all, whilst dragging companies and families through years of litigation – ‘for a principle’ or simply to rescue their own or their corporate self esteem?

Or is some form of compulsion the answer?

It is understandable that the purist mediator baulks at the idea of any form of compulsion.. One of the cornerstones of the mediation process has always been that it is both voluntary and consensual; hence the aversion to compulsion.

It is also argued that mandatory mediation simply creates a further strata of costly procedure within the legal process, and so unfairly impedes the public’s right of free access to the Courts. Moreover, it is argued that mandatory mediation achieves statistically lower success rates than mediation entered into freely. Lord Phillips, of Worth Matravers, the Lord Chief Justice, refuted this in his speech at a Conference in Delhi in March 2008, pointing out that court ordered mediation merely “delays briefly the progress to trial and does not deprive a party of any right to trial”, and that “mediation is ordered in many jurisdictions without materially affecting the prospects of success”.

Apart from cases where a definitive ruling on the law is required, or an injunction is sought; or the visibility of the litigation is desirable, the most common reason for refusing to mediate is the litigant’s firmly-held belief that he or she is wholly in the right, and that therefore there is no need to compromise. Yet it remains commercially indefensible to continue in dispute with another where there is an alternative possibility of early resolution. Lord Phillips, at the same Conference in 2008 stated:

“It is madness to incur the considerable expense of litigation - in England usually disproportionate to the amount at stake - without making a determined attempt to reach an amicable settlement."

Sir Anthony Clarke, Master of the Rolls, echoed this sentiment in his speech to Grays Inn in June 2009, stating: “only a fool does not want to settle”.

The Answer

It is time that we considered forcing the horse to water, yet without necessarily forcing it to drink. Mandatory ADR is happily accepted in many parts of the world, from the American States and parts of Canada, through Norway and Sweden, to Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and China.

There is no constitutional bar to mandatory mediation in the UK. Article 5(2) of the EU Directive in effect permits our national legislation to make mediation compulsory, providing it does not deny the parties their right of access to the courts.

Positive sentiments upon mandatory mediation have been echoed by senior members of the judiciary. Sir Anthony Clarke, Master of the Rolls, in his speech to the Civil Mediation Conference in May 2008, referred to the fact that “the courts may well have the power under the CPR as they stand to direct mediation”; and in his speech to Grays Inn in June 2009, he identified court’s case management powers under CPR 1.4(2)(e), as permitting “such orders to be made routinely at allocation or as anticipated by CPR 26.4(1)”. Sir Anthony repeated these views at a FOIL sponsored debate on mediation in personal injury litigation in London in January 2009. Judge Paul Collins, the senior judge at CLCC, has voiced his support of compulsory mediation as an automatic stage in the court process, as has Robert Nicholas, when head of the Proportionate Dispute Resolution team at the Ministry of Justice.

In Bradley v Heslin [2014] EWHC 3267 (Ch) Mr. Justice Norris came as close to advocating mandatory mediation as any other judicial or governmental announcement. In his judgement, Norris J. expressed dismay at finding himself trying a case about a pair of gates – a case that ultimately resulted in the parties incurring legal costs totaling well over £100,000, and where the cost of installing electric gates, that might have resolved the dispute, would have cost only £5,000. In what might be seen as clear exasperation, the learned judge declared:

‘I think it is no longer enough to leave the parties the opportunity to mediate and to warn of costs consequences if the opportunity is not taken. In boundary and neighbour disputes the opportunities are not being taken and the warnings are not being heeded, and those embroiled in them need saving from themselves. The Court cannot oblige truly unwilling parties to submit their disputes to mediation: but I do not see why, in the notorious case of boundary and neighbour disputes, directing the parties to take (over a short defined period) all reasonable steps to resolve the dispute by mediation before preparing for a trial should be regarded as an unacceptable obstruction on the right of access to justice’.

In cases where settlement is not reached in the mediation, a mediator can remain usefully engaged by facilitating agreement upon further directions or lists of issues, so that the process would considered ‘a complete waste of time’. Even where the judiciary are not entirely convinced of compulsory mediation, they are virtually unanimous in agreeing that “robust encouragement” must be given to mediate. This robustness will inevitably increase with time, and the line between encouragement and compulsion will gradually be eroded. Protracted litigation is one of the most destructive elements in society: it destroys businesses, breaks up marriages, and damages health. There is therefore an urgent social need to dissuade our neighbours from unnecessarily entering into prolonged disputes.

But if persuasion through commercial logic cannot work, then some form of compulsory mediation is the natural, obvious and most effective answer.

Government intervention – or a Makeover?

The mediation community has been encouraged by the repeated remarks of Government ministers and other leading figures, expressing their determination to promote mediation.

But this will not happen unless the Government grasps the nettle and makes mediation compulsory - or alternatively, unless mediation undergoes a major marketing makeover. Or both.

The marketing conundrum presented by the Carpet Cleaner analogy demands an explanation. A prudent manufacturer in such circumstances would ask: “Where are we going wrong? Should we re-package the product, or present it in a better light? Or should we withdraw it from the market altogether?”

The Search for Justice

The root of the problem is that most parties in dispute seek only one thing: “justice”. – and they associate justice and fairness only with Judges and the Courts. Parties have a remarkably naïve faith that the one person who will vindicate them is the Judge. It matters not that their lawyers, their experts, their friends and spouses may all have advised them to abandon the litigation: they remain driven by the firm conviction that the judge will see that they are right. And if the Judge does not see that they are right, then the Court of Appeal will. And if the Court of Appeal does not, then the Supreme Court will. We are thus victims of the success of our judicial system. Disputants have a deep-seated unswerving respect for our courts and judges. This often makes their expectations of the judicial process wholly unrealistic. They “want their day in court” because they see it as their only path to outright vindication – and justice. And why should they explore an “Alternative Therapy” such as mediation, when there is a long-established, well -trodden road through the courts?

We need to educate the public into accepting mediation as an equally effective route to justice. But turning people away from litigation and into the arms of mediators may prove a daunting challenge. Mediation will never be able to compete with the courts on a level playing field. It cannot offer the degree of vindication that parties crave, nor the measure of public humiliation of the opponent they seek, nor the huge sums of money that they so readily anticipate.

This is why, without some degree of compulsion, the Government may never be able adequately to turn back the tide of litigants from the courts.

Marketing or Selling

Theodore Levitt, the American economist and retired professor of marketing at Harvard Business School, in Marketing Myopia, Harvard Business Review (1960), described the difference between marketing and selling in this way:

"Selling concerns itself with the tricks and techniques of getting people to exchange their cash for your product. It is not concerned with the values that the exchange is all about. And it does not, as marketing invariably does, view the entire business process as consisting of a tightly integrated effort to discover, create, arouse and satisfy customer needs.”.

In other words, marketing involves more than simply getting customers to pay for the product: it involves developing a demand for that product and fulfilling the customer's needs.

If mediation is not moving off the shelves, we must ask ourselves whether we are selling it correctly. We have tended to highlight the fact that Mediation is cheap, swift, and confidential. But many parties have no concept of how much litigation will cost, nor how long it will take. In the initial stages of the dispute they do not care how much it will cost for they believe every penny spent is a good investment. Nor are they concerned as to how long it will take, as they are similarly prepared, if necessary, to wait years to achieve redress. And they invariably want maximum publicity focused upon the other side’s unacceptable behaviour. Consequently, it may be futile to emphasise the low cost and high speed of mediation, and stressing the confidentiality of the process may equally have little attraction.

So can we improve upon the way mediation is ‘sold’? Is a make-over or re-branding the answer? If it were, the first target might be the term “Mediation”, as it may be rendering a disservice. ‘Mediation’ tends to suggest a ‘middle way’, a ‘soft and fluffy’ approach, or even Meditation. The Government wants mediation taken up at increasingly earlier stages in disputes; yet it is precisely in those initial phases that parties want neither a middle-way compromise, nor a soft yielding attitude, but rather a crushing outright win, using the most aggressive tactics. So rather than calling in a mediator, would we feel more confident with a “Conflict Resolver” or a “Conflict Negotiator”?

The problem is that mediation is an intangible concept, yet we try to sell it with one message for all, at all times. A compromise might be attractive to one litigant, but not to another; it may be unattractive at the outset, but become more attractive later. Similarly, the ‘cheaper and swifter’ arguments may have great weight with some parties at some times, but not with all, at all times.

Market Research

If we are to entice litigants away from the courts, we need to sell mediation differently, perhaps emphasising more the opportunity to effectively vent and communicate views in a safe environment, or to secure an apology or explanation, or to retain control of the outcome, or simply to achieve a dignified exit from the dispute.

But the mediation fraternity is utterly dysfunctional when it comes to marketing. Has any proper market research been conducted to assist mediation providers in promoting their product? Have we made any real attempt at identifying the needs of our target markets, or the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviour patterns of our public? Some proper and comprehensive market research might be a prudent first step for any commercial entity faced with the mystery of creating a good product that is not selling. It might be thought essential bearing in mind we are faced with a highly resistant public.

But such research will not be without its problems: mediation is multi-layered as well as intangible: mediators maintain it is applicable to most groups in most sectors across the board. So how can any one group be effectively targeted in research? Effective marketing would also require the proliferation of ‘stories’ demonstrating how mediation achieved a just and fair result, how commercial and domestic situations were made better through mediation, and how the process was able to restore dignity and self-respect to deeply entrenched parties.

But thoughtful re-modelling may not be enough. In the current economic environment it is a commercial imperative for Government to ensure that no sector squanders its much-needed funds on unnecessary destructive litigation. The only real alternative, therefore, is some robust Government intervention, rendering it virtually impossible to litigate without first considering mediation. In this way we may see mediation taking its rightful place, alongside the courts, as a primary method of conflict resolution.

Paul Randolph

October 2015