What was the early RCM really like? What we know about the student experience, expectations and musical standards.

Until relatively recently, musicological custom and practice – because of its concern to historicize the lives and works of composers belonging to the high art tradition – worked against a rounded understanding of late nineteenth-century British musical life. The traditional historical narrative of this period (together with its attendant English Musical Renaissance trope), was established by writers determined to treat British music’s high art aspirations on a different level from other sorts of contemporary compositional endeavour, while ignoring musical practice completely. The artificiality (as we should now see it) of this interpretative basis, was compounded by biographers’ refusal to situate their subjects within the social, cultural and financial circumstances that made British musical life so singular. The resulting decontextualization significantly misrepresented the reality of what was a vibrant and participative British musical culture. British musical life (as George Grove observed in his Dictionary’s Preface) was fuelling significant economic growth in music publishing, instrument making and the demand for skilled teachers, while Oscar Schmitz, in his infamously-titled book The Land Without Music, observed that British audiences consumed more foreign music than did audiences elsewhere.

It is perhaps not so surprising that British variance with European musical practice should have also extended to the sphere of professional training. In 1866, the Society of Arts Report comparing the state of musical education between the Britain and in Europe drew attention to the gap between the quality of systematic musical training offered by representative continental conservatoires and that of the RAM. And when, eventually, the RCM was established in 1883 (part of the new wave of music colleges set up across Britain around that time), there was the impetus to establish it along rather more professional lines than its historical predecessors. But for various strategic and diplomatic reasons (one of which was establishing the joint College and Academy examining board, the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music), it became more expedient to mask, rather than to proclaim, the significant differences between the musical scope and educational quality offered by the RCM and that of the RAM and the National Training School for Music. But this blurring of the RCM’s radical nature also underplayed the impact on British musical culture that its early generations of students made in all sorts of areas, not just composition. We therefore have much to learn by discovering what exactly motivated early College students to study at this new institution; whether their decision to do so was financially rational; and what sort of professional and personal objectives the RCM opened up for them.

Drawing from my archival research of the earlier RCM, today’s paper explores some of the characteristics of the College’s student body in its first thirty years, before the format and attitudes of Victorian and Edwardian society were ruptured by the First War. It is revealing to consider aspects such as the musical and social implications of the different scholar and fee-paying student constituencies; the significance of the ARCM and the types of candidates taking it; and also, the question of student standards (this latter is particularly interesting, given that there was then no entry exam for fee payers). In the process, I shall talk about the types of musical experience that the College offered its students, and how these help to explain why it was possible for the RCM to establish its reputation within such a relatively short time.

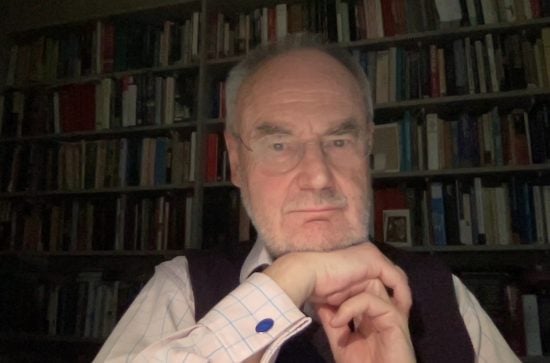

David Wright

Professor of the Social History of Music, Royal College of Music, London

David Wright initially worked as an organist, training with Dr Philip Marshall at Lincoln Cathedral and with Harry Gabb at Trinity College of Music, before undergraduate and postgraduate (historical musicology) studies at the University of London, Goldsmiths’ College. He then taught at both TCM and Goldsmiths’ until he was appointed a member of Trinity’s senior management in 1994. He moved to the RCM in 1997, where he was Head of Postgraduate Studies and later Reader in the Social History of Music. He has returned to the RCM as a Research Fellow.

He was a convenor of the ‘Music in Britain’ seminar held at London University’s Institute of Historical Research while working informally with the economic and social historian, Cyril Ehrlich, a formative influence on his making the decision to concentrate on researching British music’s social history. Since 2002, he has written on a broad range of subjects, spanning from the culture and economics of John Stainer and Victorian music publishing, to the entity and repertoire identities of the London Sinfonietta. Recently, he completed a history of the RCM (The Royal College of Music and its Contexts: An Artistic and Social History (Cambridge University Press)). His account of the ABRSM, (The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music: A Social and Cultural History (The Boydell Press)) was supported by a British Academy award, and investigated the ways that grade music exams established and helped to define British musical taste. With Nick Kenyon and Jenny Doctor, he co-edited The Proms: a new history (Thames & Hudson), writing the chapter about the Prom seasons of William Glock and Robert Ponsonby.