One research area is the question of translators as cultural intermediaries, in Ireland and in France, as they open up and call into question the idea of a national literature and as they are instrumental in the formation of a world literature. Translator roles are important here: as an intermediary the translator can be an exhibitor, a teacher, a tourist, an editor, a spokesperson. With translations of literary texts arising from conflict situations, the main questions are how translators deal with such a text, and why they translate in the way they do. Like the author in a conflict situation, the translator moves between reading and writing, and in the process of performance and mimesis of traumatic events, can be drawn to elide, alter, repeat and fragment narrative components.

An ongoing research project (to appear in 2016) is the question of the English language in France today. During the period 1990-2010 globalization brought about a decline in the power of the nation state. The French language, as one of the foundation stones of Republican nationalism, as well as its promotion and defence, has given rise to many studies. From the twentieth century to the present the subject of the crisis of French – its paradoxes, its dilemmas and its blind spots – has continued to intrigue. This research uses a corpus of different types of texts in order to study changing attitudes among French speakers in France towards the English language.

Researchers are also authors, editors and readers on bilingual dictionary projects (French-English and Irish-Breton). One focus is the bilingual dictionary through time, for example, the changing aims of dictionary makers in the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Another is the modern bilingual dictionary as a tool for producing accurate sentences in the target language.

Through close study of the writings of influential Huguenots such as Pierre Bayle, the 17th century philosopher and author of the first biographical encyclopaedia, research at Maynooth University investigates some of the fundamental ideas that led to the Enlightenment in France and much of what has shaped not only French and European culture in the past but also who we have become in the present. Bayle, who has been described as the greatest French Protestant intellectual since John Calvin, was also one of Europe’s earliest journalists and defenders of religious toleration.

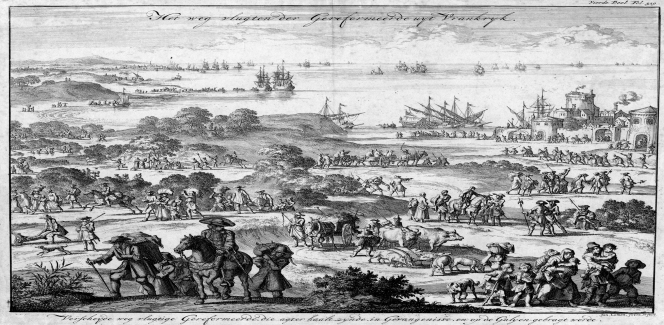

Bayle left France for exile, along with some 200,000 other members of the Reformed Church of France, the Huguenots, because of the oppressive measures taken against them under Louis XIV, which culminated in the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. They settled in a number of European countries, such as England, Holland, Germany, Denmark and Sweden, and the more adventurous travelled to America and South Africa. Some few thousand came to Ireland during that period.

The central research question driving these investigations is what happens to people when they change places. The focus is not so much on the material circumstances the Huguenots encountered, though these are not neglected, but rather on the shifts and changes in their ‘inner world’; their experience of exile; the haunting, existential questions they faced as a result of leaving France; the compromises forced on them by exile; and their efforts to make sense out of their changed lives.

How do we gain access to the ‘inner world’ of people in the past, when their social structures and material culture have been dismantled by oppressive regimes? One way into that is provided by what they write. Research focuses on narratives, texts and contexts, and, of course, manuscripts. Through the study of printed sermons, political tracts, historical reflections and, of course, Memoirs, a picture can be patiently created of the ‘mentalities’ of the Huguenots in exile, of the relationship they formed with the societies in which they settled, and the tensions that inevitably arose when the expectations of the refugees differed from those who granted them refuge. The work being carried out on the Irish Huguenot Refuge concentrates particularly on the religious culture of the Huguenots in Ireland and on certain key figures, such as Jacques Abbadie, Élie Bouhéreau, Isaac Dumont de Bostaquet and Jacques Fontaine.

This work on the writings of Huguenot refugees has opened up other areas of study, notably of ‘ego documents’ and life-writing, letters and journals. Huguenots, unlike the English Puritans, did not tend to keep journals of their inner life, and a lot of their ego-documents got lost when they fled France. But some archives survive and their manuscript holdings are being mined for what they can tell us about the history of emotion, friendship, relationships between parents and children, motherhood, and, of course, the way religious faith shaped and structured not just a way of being but a way to resist.

Some wonderful narratives emerge from these documents that challenge assumptions about what it meant to be Protestant, whether in France or in exile in this period. The intellectual and moral seriousness of French Reformed culture emerges from the correspondence of Pierre Bayle and the letters written to Élie Bouhéreau, which provide many insights into what these young men were imbibing from their education, reading, and social networks. But their letters also offer unexpected glimpses of card-playing, dancing, theatre-going and flirting, and, above all, of what made them laugh. The letters and life of Élie Neau, a French mariner and later sea captain, who had settled in British America, sound another note entirely. Captured by privateers when he was on the way to Jamaica, he was brought back to France and, as a Protestant who had fled the kingdom without permission, sentenced to a life of captivity on the galleys. Unexpectedly pardoned as a result of diplomatic intervention, Neau returned to New York; but he had been changed by his own experience of slavery, and he went on to become an advocate for black slaves there. Such stories unearthed in the archives add to our understanding of the past; they also add colour and depth to our collective memory and our sense of how we came to be who we are in the present.

While France and French culture have influenced many countries across the world, France itself has also experienced a variety of influences, not least in waves of incoming migrants. While the arrival of the Franks and the English occupation in the medieval period did not happen at a time when France as we know it existed, later inward migrations such as that of the Italians in the 16th century left traces which are still visible today in architecture, art and theatre. One such migration was that of the Irish, who began arriving in numbers in France around the year 1600. Between then and the French Revolution, the Irish were the most numerous immigrant group in France according to one recent French historian of foreigners in France. Research carried out in Maynooth University has brought to light substantial numbers of predominantly Catholic Irish in France during the period 1590-1690, in addition to the previously well-known migration of the ‘Wild Geese’ in the next hundred years. This research has taken place in parallel with the Irish in Europe project based in Maynooth University for many years now.

The Irish ancestors of several iconic French figures arrived in France during this time: the first president of the Third Republic, General Patrice de MacMahon was of Irish descent, while General de Gaulle’s great-grandmother was Angélique McCartan, a descendant of the McCartans of County Down who arrived in France at the end of the 17th century. Studies have been carried out at Maynooth University on how the memory of this migration has been constituted in archival sources, in historical studies, in French literature and no less importantly in family memory. This has brought to light families whose move to France occurred in the mid-17th century, earlier than the ‘Wild Geese’ are usually thought to have migrated en masse to France. These families have maintained an awareness of their genealogy and in some cases buildings, artwork and other objects have survived as witnesses of this history. This family memory shows how founding moments of historical phenomena can be highlighted or occluded in subsequent times, when history is written. The case of the most famous Irish writer to live in France before Wilde or Beckett, namely Antoine Hamilton (1644-1719) confirms the importance of the 1650s in Franco-Irish relations: Hamilton moved to France with his parents at this time. His works were later much admired by figures such as Voltaire for their acerbic wit and polish, and were referred to as models of French style, proving that Hamilton had perhaps become more French than the French themselves! A current project at Maynooth University is studying Irish writers in France in that period, particularly Hamilton and the quadrilingual poet Manus Ó Ruairc (c. 1658-1750) and their writing in and of exile.

Unlike other migrations into France, the Irish migration did not affect the French language. However, many Irish family names survived in France and some still do. How these names were changed and how their bearers assimilated into French society is a study which combines linguistic and historical methods in order to chart the evolving reality which is typical of all migrations. Irish migration to France since 1600 has also left traces in the educational and clerical fields. Contacts maintained down to quite recent times include well-off families in Cork sending children to be educated in France and relations between some Irish and French dioceses.

Migration into France is an age-old phenomenon, contrary to what might appear from debates in the country in recent decades. The Irish are one of many groups who blended into French society and made it what it is. France is also a country of internal diversity and teaching and research in Maynooth University has developed this perspective over many years. Breton is taught in Maynooth University along with other European languages such as Catalan. Its study and the study of regionalism and regional literatures in France in Maynooth University helps to highlight the variety and the richness of language, literature and culture in France. In addition to teaching of Breton language and its culture, works have been published in the fields of lexicography and translation of literature to and from Breton.

Within French Studies at Maynooth, a common strand of research focuses on women’s writing in French, over a period ranging from the mid-20th century to contemporary writing. One aspect of this is the question of gender and authority as it affects women writers. Research here has shown a multiplicity of strategies, textual and otherwise, used to assert authority and to counteract various cultural stereotypes relating to women writers. This applies particularly to writers of the mid-20th century, such as Marguerite Yourcenar. However, the study of more recent, contemporary authors (such as Marie Darrieussecq, Christine Angot, Marie Ndiaye and others), has shown a shift both in cultural perceptions and in the way women writers themselves approach the issue.

A related topic under investigation is the issue of authorship, what it may represent for women writers, and how it may be evolving in the contemporary period. This study of authority and authorship also extends to women authors from outside mainland France, particularly those of North African origin, for example Assia Djebar.

In terms of subject matter, a range of approaches can be observed, from ‘autofiction’, concentrating on individual, direct experience to a writing which incorporates elements of fantasy, as evident in the work of Marie Darrieussecq and Agnès Desarthe, and in a different vein, that of Marie Ndiaye. These trends are to be studied both within the French context and from a comparative perspective, investigating what common threads – and what differences – may be found in contemporary women’s writing from different cultural areas, expressed in different languages.

It is also planned to broaden the study of this area to include contemporary women writers in North Africa, such as Assia Djebar and Leila Sebbar. Women writers from other Francophone countries are already the object of investigation. For example, in terms of Quebec women’s writing, authors such as Gabrielle Roy, France Noël and Ying Chen have already been the focus of a number of departmental publications and continue to inspire a rich variety of research questions. In addition, gender and its representations have been studied in relation to the Hungarian-Swiss writer Agota Kristof.

The final specialist area in relation to women’s writing in French is that of ‘maternal counternarratives’. An increasing number of contemporary women writers in French are experimenting with the textual space as a means of defying the oppressive norms of motherhood and according a voice to ‘other’ mothers or ‘transgressive’ mothers, those whose behaviour does not conform to societal expectations. Such texts trace a trajectory of atypical mothering whose features incorporate feelings of repulsion at being pregnant and disgust with the physical changes brought on by pregnancy; over-mothering, emotionally suffocating the child, exerting excessive control over the child’s life; ambivalent mothering, being both repelled by and drawn towards the child; incompetent mothering, not meeting the child’s basic needs; outright rejection of motherhood, aborting or abandoning a child, or deciding not to have children; child-abuse, psychologically or physically or both; and, finally, at the extreme end of the scale, infanticide. Authors who whose writing corresponds to the term ‘maternal counternarrative’ and whose work is being examined include, inter alia, Eliette Abécassis, Nathalie Azoulay, Geneviève Brisac, Pascale Kramer, Véronique Olmi and Mazarine Pingeot.