From Booterstown to Burma: The Irish Buddhist tried for sedition in 1911

Toggle

In January 1911, central Rangoon shut down to support an Irishman being tried for sedition. The Chinese, Indian and Burmese bazaars closed and crowds carried him in ceremonial procession to the court. The cinema donated two days' takings to his defence fund, one of Gandhi’s close allies threw his newspaper’s weight behind him and his lawyer was a leading Burmese nationalist. The Irishman supported by this ethnically and religiously diverse coalition was a Buddhist monk and he was on trial for challenging Christian missionaries.

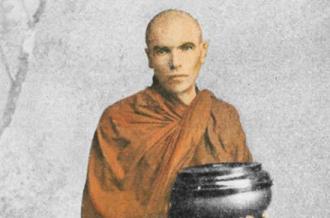

Born Laurence Carroll in Booterstown in Dublin in 1856, he had worked his way across the Atlantic, hoboed across the United States and sailed the Pacific before winding up as a docker in Burma where he was ordained as U Dhammaloka. Along the way, he learned the activist skills that helped him become a leading anti-colonial celebrity across Buddhist Asia, including today’s Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Japan. Between 1900 and 1914, he led wildly successful preaching tours, set up multi-ethnic Buddhist schools, published and distributed huge numbers of radical pamphlets, and became a key player in the transnational Buddhist revival.

However, 1911 was not Dhammaloka's first brush with the law. He was a man with five different aliases and, despite loving to tell his story, he remained silent about 25 years of this life, details of which were presumably too risky to share in public. Beside his trial, we find him under police surveillance, the subject of an early extradition-type request, faking his own death and eventually disappearing. In Rangoon, the scale of popular support was such that the trial was postponed and his eventual sentence – binding-over to keep the peace – as minimal as possible without actually clearing him.

But why was Dhammaloka so popular? And how can we make sense of an Irishman abroad being a Buddhist opponent of Christian missionaries?

In Asia as in Ireland, colonialism had a religion problem. Empire was increasingly justified "at home" as bringing the Gospel to the heathen, but it could not tread too heavily on local religion in the process. Just as Daniel O'Connell could mobilise Catholicism for his political purposes, Empire’s support of missionaries in Asia left a space for anti-colonial activists to organise around the defence of local religion, be it Islam, Hinduism or Buddhism.

Dhammaloka for his part had clearly fallen in love with traditional Burmese Buddhist culture and was horrified at the impact of colonialism. He described it as bringing "the Bible, the whiskey bottle and the Gatling gun" in

a programme of conversion, cultural destruction and military conquest. His targets were often more specific: for example, colonial officials’ practice of taking native "wives" without legal marriage, only to abandon them and their children on returning to Britain (or Ireland) and marrying "white" women. Small wonder that the authorities found him a threat, or that he was wildly popular in many quarters.

He was a man with five different aliases and remained silent about 25 years of this life, details of which were presumably too risky to share in public

Central Burma had only been finally conquered with a brutal counter-insurgency campaign less than a generation previously, in which Irish people had played a very different role. The Burmese Buddha statue in Molly Bloom's soliloquy, which greeted visitors to the National Museum for many years, was probably looted. It was presented by Col. Sir Charles Fitzgerald as "a trophy of Britain’s newest colony exhibited to the people of her oldest". In these circumstances, the Bible and the bottle were safer targets than the Gatling gun, but even this was sailing close to the wind.

The spectacle of a westerner "going native" – wearing local clothing, begging as monks do, ritually subordinated to Asian hierarchies, working with all sorts of local networks and speaking local languages – was threatening enough in itself, particularly if the Buddhist was Irish. Much of the colonial army was Irish, and bestselling novels like Kim and The Road to Mandalay depended on anxieties about the intersection of Irishness, the military and conversion to Buddhism.

The Irish Buddhist: the Forgotten Monk who Faced Down the British Empire by Dr Laurence Cox is published this week by Oxford University Press