How Joe Biden's Irish ancestor saved thousands of lives during the Famine

ToggleHow Joe Biden's Irish ancestor saved thousands of lives during the Famine

Edward Blewitt's public work schemes in Co Mayo contributed to the survival of thousands of people and altered the county's landscape, writes Dr Ciarán Reilly, Department of History

But Blewitt was no ordinary Famine emigrant. During the previous five years in which a million or so of their countrymen and women had died, he had contributed to the survival of thousands of people in the Ballina area by overseeing work on the public relief schemes. Though beneficial, this work was quickly lost to social memory.

On June 22nd 2016, thousands of people lined the streets of Ballina to welcome Edward Blewitt's great-great-great grandson, Joe Biden, back to his ancestral home. The visit by the then US vice-president to the site of the Blewitt home on Garden Street was a private affair away from the huge media presence which had gathered in the town. I was chosen to brief the vice-president about the role of his ancestors in overseeing the public works scheme during the Famine. Joined by his brother, sister and grandchildren Biden was particularly anxious for the latter to learn about their ancestors and the Great Famine.

The Famine narrative has obviously been dominated by death, disease and hunger, but what of those that survived? How did people survive the Famine? In briefing Biden, I wanted to highlight that important part of the Famine story, which is often overlooked. Having heard the story, Biden, accompanied by then Taoiseach Enda Kenny, interjected "do you hear that, we should be very proud!"

Ballina was decimated by the Famine, ranking alongside Skibbereen and Kilrush as the most hunger-ravaged parts of Ireland, and the Blewitts witnessed hunger and disease on a daily basis. When the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle visited Ballina in the summer of 1849 he remarked that the town’s population was "gone to workhouse, to England, to the grave".

Hunger and desperation drove hundreds to the workhouse which had been established on the eve of the Famine. It was a brutal regime, where the poor and diseased were huddled together and described in one recent account as being a "grim bastille of despair". Simply put, people rather would die in the ditches than to enter the workhouse. It was not by accident then that every workhouse in the country contained a cemetery at the back of the premises, as this was where most ended their days.

Built to accommodate 1,200 people, there were almost 3,000 people huddled within the walls of this charnel of death in Ballina by late 1847. In December, it was alleged that the inmates of the workhouse were left without food for a number of days such was the dire financial straits of the guardians who oversaw the management of the poorhouse. The union had ran out of money and the ratepayers who had previously supplemented the cost of maintaining the poor were themselves on the brink of disaster.

Investigating the allegations, the Relief Commissioners at Dublin Castle sent a Lieutenant Hamilton to ascertain what was happening in Ballina's workhouse. His report depicted the appalling mismanagement of the union and the board of guardians were quickly disbanded as a result. To avert further death in Ballina, the relief commissioners believed that a scheme of outdoor work was needed. Lieutenant Hamilton suggested that a general overseer be appointed to superintend the works, someone who had the right credentials and the ability to save lives in the process.Enter Edward Blewitt. He had already been involved in two of the largest mapping endeavours of the 19th century – the Ordnance Survey in the 1830s and Griffiths Valuation in the 1840s - and was sometime employed by the parish vestry to value and plot land for the payment of tithes. He had a working relationship with Henry Brett, then county surveyor of Mayo who was responsible for famine relief efforts in the county. Taking them from the dreaded workhouse system, Blewitt’s judicious management of the scheme kept thousands alive building roads and carrying out drainage work.

What Blewitt probably didn’t realise was that it was a thankless job. Death stared him at every turn and there were difficult decisions to be made. Almost immediately, he was informed that there were people who were ineligible or defrauding the system claiming a position on the scheme when they were entitled to do so. To rectify the situation, Blewitt was informed that a test should be applied which effectively removed those who did not want to work or who were not entirely dependent on the scheme for survival. It was a difficult task but necessary for the system of relieving the poor to continue in the locality.

Blewitt’s work was also obstructed by disgruntled workers who complained about their pay, conditions of work and the quality of the tools that they had been given. Many of the workers simply broke hammers and other implements to prevent them from having to work. However, Blewitt soon overcame these problems and the Ballina works were praised for the efficiency.

One of the great problems with relief works was that the hungry were often forced to walk several miles in the morning and perform work with little food. Blewitt was faced with the predicament that in saving lives many others would succumb to death. To prevent this from happening, Blewitt began to place the men working on projects close to their homes and replaced the arduous journeys that they undertook.

Although public works schemes were often derided as simply involving building roads going nowhere, the works overseen by Blewitt were progressive and helped to alter the Mayo landscape in the process. Praised as being ‘zealous’ in his duties, Blewitt oversaw the construction of new roads linking places such where transport had been difficult in the past.

Blewitt also oversaw drainage works allowing for greater cultivation of the land. This was made possible by the introduction of the land improvement loans and which allowed landlords to carry out necessary improvements in the process. In October 1848 a member of the Society of Friends (or Quakers as they were known) visiting Ballina pointed out the important work that Blewitt was overseeing. Walking the land with Blewitt, he commented that the progress in drainage and cultivation was very evident.

He continued in the role until 1850, although the scheme was greatly curtailed the previous autumn. Without the collection of rates, the provision of relief on a long-term basis became problematic. Most of the leading landowners in the county were unwilling, or unable, to pay what they owed towards rates and the maintenance of the poor. Overseers, including Blewitt, were owed salaries and the union was once more in chaos with debts of over £20,000 by September 1849. Although the committee recommended that the overseers should be amongst the first group of people to be paid, Blewitt’s time in Mayo was drawing to a close.

Blewitt then had a decision to make: remain in Ireland in a town ravaged by hunger and disease, or undertake the perilous voyage of emigration to the unknown and America. He chose the latter. Once again, Blewitt’s resilience shone through and he had established himself as a ‘land surveyor’ in Scranton, Pennslyvania within a decade. His family prospered there and laid the foundations for others from Co Mayo to join them.

Edward Blewitt died tragically in 1872 near Scranton, more than 20 years after he had helped alleviate the plight of the poor during the greatest catastrophe of 19th century Europe. His descendant faces similar difficult decisions today should he be elected to the White House next month. Resilience is one of the virtues that many political commentators have ascribed to the 2020 presidential candidate having overcome many personal and professional difficulties in his lifetime. Blewitt displayed this virtue too and in doing so helped others during Ireland’s darkest hour.

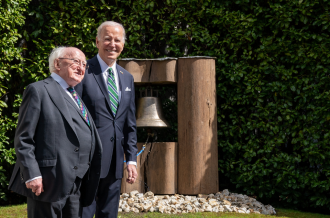

Joe Biden Image Credit:

The White House, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons