The story of Ireland's first socialist commune in 1830s' Clare

Toggle

In 1830, the Clare landlord John Scott Vandeleur was driven to desperate measures. The area around his estate at Ralahine had seen a simmering of peasant violence that suddenly boiled over with the murder of his steward, Daniel Hastings.

Eight years earlier, Vandeleur had listened to Welsh socialist Robert Owen promote a new vision of worker communes that he promised would improve the lives of the working class and quell their appetite for rebellion.

Vandeleur decided he had no option but to act – and so began Ireland’s first ever socialist commune. The landlord called upon an English socialist, Edward Thomas Craig, to implement Owen’s ideas in Ralahine. Years later, Craig would write that groups known as the ‘Terry-Alts’ and the ‘Lady Clare Boys’ paraded the countryside with firearms, disguised in extravagant costumes and perpetrating ‘acts the bare recital of which made the heart palpitate’.

While Craig describes the locals’ initial suspicion of his motives, he and Vandeleur found 52 peasants before long who were willing to take part in the experiment. Craig drew up the society’s laws, which, in addition to the key principle of communal work, also included a ban on alcohol and tobacco. The farm’s stock and property was to remain Vandeleur’s until such point that the society could purchase them, after which they would be owned in common.

|

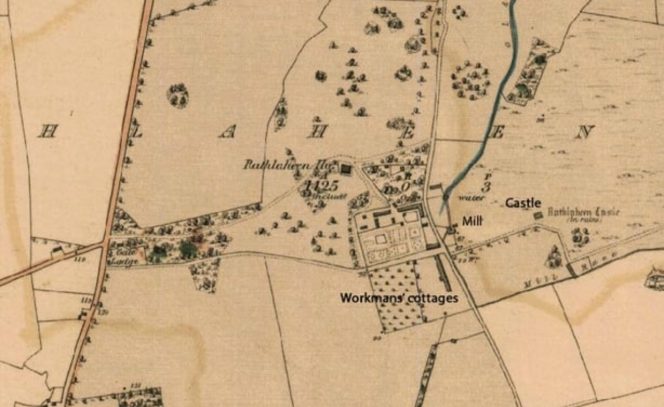

| 1842 survey map showing Ralahine estate, with the location of buildings still standing also marked. Credit: Singersong Blog https://singersongblog.me/ |

Instead of a steward, the society was governed by a committee of nine members, chosen every six months. There was also a ‘suggestion book’ to encourage each member to offer recommendations. The peasants had to continue paying £900 in annual rent to Vandeleur, which historian Cormac Ó Gráda has shown to have ‘substantially exceeded the national average’.

Nevertheless, the commune appears to have been an immediate success. Harvests were extremely good, while the peasantry’s appetite for rebellion dissipated. They even embraced modern technology, becoming the first users of a reaping machine in Ireland. Before this, the people of Ralahine had been suspicious of such technology, while Vincent Geoghegan notes that a similar machine had recently been destroyed by peasants elsewhere in Ireland.

Vandeleur was quick to reassure the workers that such technology, which would normally reduce wages or result in job losses, did not bring such threats when operated on a co-operative commune such as theirs. The peasants of Ralahine were clearly economically literate enough to know that modernisation without job security counted for little.

|

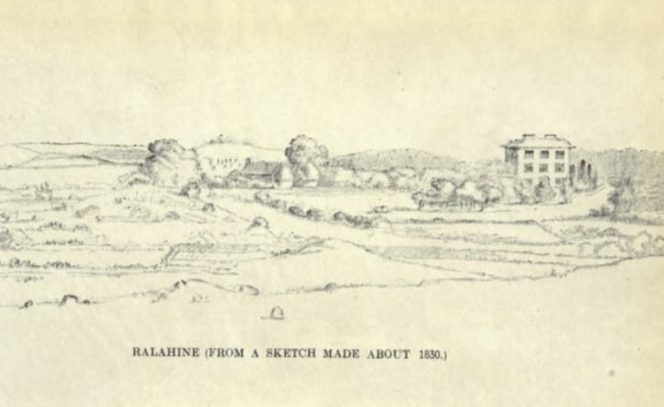

| "No amount of harvesting or modernisation could save Ralahine from the vagaries of landlordism". From An Irish Commune: The History of Ralahine by Edward Thomas Craig |

Despite the ban on alcohol and tobacco, there remained room for frivolity, such as a festival held to celebrate the harvest. Craig tried to introduce the workers to the English country dance, but instead ‘the Irish jig maintained its supremacy among the adults’. It was, however, ‘an easier task to train the children to the mazes of the quadrille’, which Craig claims had a positive impact in ‘training them to order, method, discipline, and courtesy’.

While seemingly innocent, this anecdote does show that Ralahine remained a colonial project in spite of its noble ideals. There remains a sneaking suspicion that the commune’s secondary purpose was to find a more benign way to ‘civilise’ the Irish and eradicate national traditions.

But no amount of harvesting or modernisation could save Ralahine from the vagaries of landlordism. One night in 1832, Vandeleur gambled away the estate in Dublin. He fled the country, while the arrangements made by Craig and the Ralahine workers held no legal standing and they were evicted. The members did, however, leave a declaration, in which they stated that for two years they had experienced ‘contentment, peace and happiness’. Given that Craig emphasises the illiteracy of the workers, it is probably impossible to ever truly know if these were the workers’ own words, or to predict how the commune would have fared during the disastrous years to come.

When Ireland eventually secured its freedom, James Connolly arguged it should be based on 'the social arrangements of Ralahine'.

Ralahine would live on as a model of what might be possible in a future, socialist Ireland. Craig's account was first published in 1882, sparking a renewed interest in the commune. In 1909, the socialist-leaning paper The Peasant featured an article on Ralahine, while The Irish Nation had a series of articles the following year by Revivalist writer Standish O’Grady in which he set out his proposal for the establishment of 'the first modern Irish commune’.

The editor of both papers was W.P. Ryan, a socialist writer from rural Tipperary, who would later go on to write about Ralahine in his history of the Labour movement. Ryan's novel The Plough and the Cross and long poem Feilm an Tobair Bheannuighthe feature co-operative farms that have much in common with Ralahine.

But undoubtedly Ralahine’s greatest promotion came when James Connolly devoted a chapter to it in his 1910 book Labour in Irish History. Calling it an ‘Irish Utopia’, Connolly argued that when Ireland eventually secured its freedom, it should be based on ‘the social arrangements of Ralahine’. The story of Ralahine confirmed Connolly’s belief in what he called ‘Celtic Communism’, where pre-colonial Ireland was organised on ‘the Gaelic principle of common ownership’.

Ralahine’s legacy even went far beyond Ireland. The Austrian Zionist writer Theodor Herzl namechecks the commune in his novel Altneuland, in which the hero declares the kibbutzim being built in Palestine as ‘thousands of Ralahines’. That Ralahine should find itself referenced in a Zionist text is perhaps reflective of the complicated intermingling of utopian socialism and colonialism that it represented. One cannot help but wonder what the ordinary men and women of Ralahine would have thought of such a legacy as they were marched beyond its boundaries in 1832.

This piece originally appeared on RTÉ Brainstorm.