What can we expect from the 2024 local elections?

ToggleLocal election contests are an important bellwether of how political parties and groupings are faring in the run-up to the next general election, write Dr Adrian Kavanagh and Caoilfhionn D'Arcy of the Department of Geography.

While most analysis on a national level will be focusing on the European elections, the local election contests are a more important bellwether in terms of how political parties and groupings are faring in the final few months leading up to the next general election. A list of high profile, well-known candidates can enhance a political party’s prospects in the European elections, sometimes irrespective of the underlying changes in political support trends.

However, local elections tend to offer clearer signposts in terms of how political parties and groupings will fare at the next general election. For instance, the collapse in support levels for the Fianna Fáil-Green Party and Fine Gael-Labour governments at the general elections in 2011 and 2016 were well flagged by poor performances for these parties in the preceding local elections in 2009 and 2014, respectively.

The greenani, which saw big gains for the Green Party in the 2019 local elections, also swept into the general election contest months later, with their number of TDs increasing from two to 12. But this is not a hard and fast rule. The poor Sinn Féin performance at the 2019 local elections appears to be an anomaly given the level of gains made by that party at the 2020 general election.

Geographical trends in local elections also act as useful signposts as to where political parties and groupings can hope to make gains, or should be worried about potential seat losses, at a subsequent general election. If a political party is making significant gains in the electoral areas that largely correspond to a general (Dáil) election constituency, then that party should entertain strong hopes of gaining a seat in that constituency at the next general election.

Success in a local election contest for individual candidates can potentially pave the way towards a career in national politics. A large proportion of first-time TDs will win their seats while contesting that election as county or city councillors. In the 2011 General Election, councillors accounted for 77% of the successful non-incumbent candidates (57 out 81), while they accounted for 80% (48 out of 60) of the successful non-incumbent candidates in 2016.

County and city councillors accounted for 33 of the 56 successful non-incumbent candidates in 2020 (58.9%). Another five (8.9%) successful non-incumbents (all from Sinn Féin) had been councillors up to a few months before the election, having lost their local authority seats in the 2014 Local Elections.

A successful local election campaign effectively "bloods" potential general election candidates, offering them valuable campaign experience, while working as a councillor allows them to further build up their local support base and gain a reputation for "getting things done for their local area", which are crucial elements for future success in local and general election contests.

There is a lot of geography associated with local election contests. There are more constituencies (often referred to as electoral areas for county council and city council election contests) than you would get in other electoral contests. There will be 166 electoral areas being contested in the upcoming local election contests, as compared with just three for European election contests and the 39 general (Dáil) constituencies that were used at the 2020 general election (which will admittedly increase to 43 for the next general election).

More constituencies allow for greater scope to detect geographical variations in terms of political support trends, candidate selection approaches and voter turnout levels. The much higher number of constituencies also mean that there will, in turn, be a much larger number of candidates contesting these elections. In 2019, 1,975 candidates contested the local elections, and the total number of candidates could well exceed the two thousand mark for the upcoming local elections in June.

There are interesting trends to note in terms of candidate selections at local elections. Political parties are more likely to run bigger numbers of candidates in specific regions, usually in their areas of strongest support. There is a tendency for higher numbers of women candidates to be associated with the more urban constituencies, but especially those located in the Dublin region.

Local elections are often seen as classic examples of second-order election contests; in short, election contests that are perceived to have less at stake associated with them than with first order (usually general election) election contests. Second order election contests usually also have lower turnout levels than for first order contests.

If we look at turnout trends in the Republic of Ireland over the past eight decades, the general trend is one in which turnout levels for local elections tend to be, on average, roughly 10% lower than those for preceding general election contests. But there have been occasions when local election turnouts have been higher than for the preceding general election contests in some areas.

This occurred, for instance, in 2004 when turnout levels for the local elections were higher than in the 2002 general election in a number of peripheral rural areas and some working-class urban areas. The suggestion here was that these were areas that felt detached, or marginalised, from central government, but were also more reliant on local authority services than people from middle class urban areas, for instance.

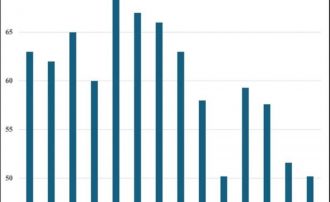

As we see from the graph above, temporal trends in local election turnout levels have tended to mirror those for general elections, with levels peaking in the late 1960s, before consistently declining over the following three decades, culminating in the record low levels (50.2% national average) for the 1999 elections. While turnout levels improved during the first decade of the 2000s, turnout levels again declined during the 2010s and the national average turnout level for the 2019 elections was on a par with the record low level for the 1999 election.

There are some interesting geographical variations at play behind these national trends. The record low turnout level of 1999 was associated with exceptionally large rural-urban turnout variations, with turnout levels of over 70% observed in a number of rural constituencies, while turnouts in the high 20s and low 30s were recorded in a number of (mainly working class) Dublin constituencies. Rural-urban turnout variations were less pronounced in the 2019 election, reflecting a tendency over the past two decades of declining rural turnout levels, contrasting with a tendency for higher levels in urban areas and especially the more working-class urban areas.

Main photo credit: William Murphy, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

This piece originally appeared on RTÉ Brainstorm