Ashleigh Wilson’s observation of a NLC at Macquarie Island this year

Friday, August 7, 2020 - 14:45

Dr Frank Mulligan, Associate Professor of Experimental Physics at Maynooth University, has collaborated with the Australian Antarctic Division to assess how the Antarctica’s upper atmosphere is responding to an increase in greenhouse gases.

A long-term study being carried out by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) will contribute to broader international climate work and research regarding the impacts of emissions. To date the research has yielded several new discoveries and insights, including:

- The upper atmosphere is cooling 10 times faster than the average rate of global warming at the Earth’s surface

- The temperatures change in response to both the solar activity cycle and carbon dioxide emissions from human activities

- A new discovery is that temperatures also vary in the upper atmosphere on a cycle of roughly four years in a phenomenon dubbed the Quasi-Quadrennial Oscillation (QQO)

The measurements being recorded at Davis research station in the Antarctic is part of a global monitoring program designed for early detection of changing climate signals coordinated through the Network for Detection of Mesospheric Change (https://ndmc.dlr.de/) and has a future goal of measuring throughout the Sun’s next 11-year activity cycle.

The measurements provide new precise information on changes in the upper atmosphere to test climate models, and suggest that ‘noctilucent’ or ‘night shining’ clouds which form in extremely cold conditions in this region are likely to show particular variability in extent and brightness that has not previously been examined.

Scanning the airglow layer

Dr Mulligan and scientists with the AAD have analysed more than 600,000 measurements over the last 24 years, 87 kilometres above Australia’s Davis research station. The research is informed by NASA satellite data and as part of the overall research, Dr Mulligan analysed atmospheric temperatures and winds as part of the team’s work.

Commenting on the research, Dr Mulligan noted: “The Davis research station record clearly shows long-term temperature variation in the upper atmosphere caused by the sun’s activity cycle, but more importantly, overlying this is an unequivocal cooling trend that is consistent with the effect of increasing carbon dioxide emissions from human activities.

“Every human being contributes a certain amount of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere during their lifetime, depending their diet, level of insulation in their homes, mode of transport, lifestyle, extent of foreign travel, etc. Most of the governments around the planet are introducing measures and incentives to reduce carbon emissions and to mitigate their effects, but each of us as individuals have a responsibility to contribute to this effort through the choices that we make in our daily lives.”

Dr John French, AAD atmospheric physicist and study lead said: “These comprise one of the longest temperature records available for this region of the atmosphere.”

Known as the hydroxyl airglow layer, it contains molecules formed by the reaction of hydrogen and ozone and emits a continuous ‘airglow’ in the night sky.

The measurements of the infrared spectrum from the airglow determine the layer’s temperature and are recorded every seven minutes throughout the Antarctic night.

Conversely to the warming that occurs in the lower atmosphere, the upper atmosphere cools in response to greenhouse gases increases.

The density of the upper atmosphere is so low, carbon dioxide actually radiates heat away into space, rather than trapping it.

“The climate of the Antarctic upper atmosphere is particularly sensitive to changes in atmospheric composition,” said Dr French.

“The hydroxyl airglow layer provides a natural means of sampling the upper atmosphere from the ground and enables us to monitor the rate of cooling induced by carbon dioxide increases.”

The study’s measurements date back to the early 1990s and have used the same, robust, precisely calibrated scanning spectrometer to scan the infrared spectrum produced by hydroxyl airglow. Dr French said the Davis research station measurements showed that cooling rate was 1.2 degrees Celsius per decade over the last 24 years, approximately 10 times the rate of average global warming (~ 1°C over the last century). ”The upper atmosphere has already cooled 3°C in the 25 years since measurements began in 1995.”

Dr French said when scientists were observing changes of one degree a decade, the calibration needed to be “absolutely precise”.

“The duration of these continuous measurements and their location in Antarctica make them unique,” he said. “There are many challenges in keeping the instrument operating, supported and well calibrated over a quarter of a century now, but it is something the AAD has done well.”

The results match those from climate model simulations and satellite measurements and provide a more precise, complete picture of the long-term temperature trend.

A new temperature cycle is discovered

Another revelation from the study is that the polar atmosphere above Davis has been undergoing a roughly four-yearly temperature fluctuation cycle of three to four degrees Celsius.

AAD climate scientist Dr Andrew Klekociuk also contributed to the study and said the find was significant.

“This variation, which we call a Quasi-Quadrennial Oscillation or QQO, appears to be linked to interactions between the ocean and atmosphere in the Southern Hemisphere, and its effects are apparent in the upper atmosphere of both the Antarctic and Arctic,” he said.

“The QQO discovery further highlights how interconnected the global atmosphere is and the importance of long-term and precise measurements for monitoring and understanding the climate system,” Dr French said.

Dr Klekociuk said it was the first time the effects of the oscillation had been identified in the global upper atmosphere, and it had implications for scientists’ ability to model climate processes, detect long-term change, and understand its effects on other upper atmosphere phenomena such as noctilucent or ‘night shining’ clouds.

Ice clouds that glow in the dark

At a height of 83 km, noctilucent clouds (also known as NLCs) are the highest in the atmosphere, on the edge of space. Composed of ice crystals, they need extremely low temperatures (around minus 130 °C) to form, and only become visible after the sun has set on the lower levels of the atmosphere. They appear to glow a pale blue, still illuminated by the sun, in a night sky.

The cooling in the upper atmosphere increasingly provides suitable conditions for NLCs to form, so they are expected to become brighter and more extensive in the years ahead.

With the cooling conditions linked to carbon dioxide emissions that drive warming elsewhere, these clouds, although spectacular, are also ‘harbingers of change’ and have been referred to as “the miner’s canary of climate change.”

The second of two papers on the research has just been published in the journal, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affecting the work of AAD scientists this coming season, the automated long-term monitoring high above Davis can continue as normal.

The Hydroxyl Spectrometer in the optics lab at Davis station

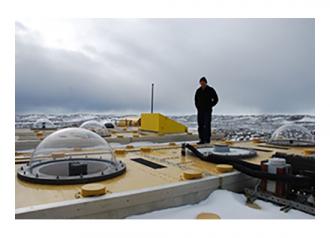

Roof of the atmospheric and space physics laboratory at Davis.

First observation of a NLC at Davis 1998

Ashleigh Wilson’s observation of a NLC at Macquarie Island this year